American Epilepsy Society (AES)

Written Comments to

Seema Verma, Administrator

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

on File Code CMS–2324–NC

Request for Information (RFI) on

Coordinating Care From Out-of-State Providers for

Medicaid-Eligible Children With Medically Complex Conditions

Submitted on: March 23, 2020

AES Written Comments were approved by the AES Council on Clinical Activities and the AES Board of Directors on March 10, 2020, and were prepared by an ad hoc, multidisciplinary AES work group comprised AES members and other experts in epilepsy care: Rohit

Das, MD, UT Southwestern Medical Center; Erin Fedak Romanowski, DO, C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan; Lisa Garrity, PharmD, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; Lisa Hawk, PharmD, UW Health; Susan Koh, MD,

Children’s Hospital of Colorado; Lidia Moura, MD, MPH, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School; and members of the AES Practice Management Committee and Treatments Committee.

About the American Epilepsy Society

The American Epilepsy Society (AES) appreciates the opportunity to provide comments to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) on coordination of care from out-of-state providers for Medicaid-eligible children with medically complex conditions,

including epilepsy. As the professional society for healthcare professionals committed to epilepsy research and care of individuals afflicted with epilepsy, the AES consists of approximately 4,000 members. The membership is composed of physicians,

nurses, advanced practice providers, pharmacists, psychologists, social workers, and basic scientists focused on epilepsy. Our commitment is to research and deliver evidenced-based care to individuals with epilepsy.

AES encourages CMS to prioritize appropriate levels of care with minimal patient and family burden. Key needs to facilitate and advance Medicaid pediatric epilepsy patient care seamlessly across states fall into five categories, as detailed and illustrated

in the following comments:

I. Appropriate levels of geographically convenient care with minimal patient/family burden.

II. Optimal use of technology and telehealth solutions.

III. Particular attention to effective care

components for children with epilepsy.

IV. Appropriate reimbursement to providers to support cost-effective, high quality care.

V. Harmonization of provider, facility, and Medicaid qualification processes across states.

I. Appropriate Levels of Geographically Convenient Care with Minimal Patient/Family Burden

AES supports measures that enable patient mobility for access to quality care and encourage access to best available geographically convenient care, without state-level constraints. Accessibility for patients and families, and patient-provider care relationships,

should be prioritized, and interstate barriers should be minimized.

Pediatric patients with epilepsy have complex, interprofessional care needs that can vary widely from patient to patient. Care at local/regional or in-state Level 4 epilepsy centers (National Association of Epilepsy Centers - https://www.naec-epilepsy.org/about-epilepsy-centers/find-an-epilepsy-center/) may be appropriate in some cases and should be encouraged where available. Geographic

convenience or timely access to care if there are long waits for appointments at large, academic Level 4 epilepsy centers also may point to local epilepsy centers as the best choice. Accessing care in a different state can be closer than going to

an epilepsy center in the state in which a patient and family resides. Regulations should enable patient access to out-of-state providers, if a state has no Level 4 epilepsy center or if a geographically closer center is in a different state. In other

cases, referrals to Level 4 epilepsy centers at large, academic institutions may be critical and should be available to patients and families without state boundary constraints.

In all cases, Medicaid regulations should support optimal patient access to quality care, whether instate or out-of-state and should not impose undue burden on patients who move or based on geographic location. In short, providers and patients with epilepsy

and their families should have choices and flexibility to determine best care solutions together.

Examples of geographic areas across the country where patients and families might benefit from reduced barriers to coordination of care across state lines include:

- A patient living in South Carolina near the North Carolina/South Carolina border is closer to a Level 4 epilepsy center North Carolina. Allowing this patient to receive care closer to their geographic location, which happens to be in another state,

would reduce family burden.

- Patients living in Northern Kentucky are closer to Cincinnati Children's Hospital in Ohio than to in-state epilepsy specialty care centers. Similarly, patients residing in parts of West Virginia with limited access to pediatric epilepsy specialty

expertise find that appropriate care is geographically more accessible across state lines in Maryland, Virginia, or Washington, D.C.

- A patient who had been living and receiving care at a Level 4 epilepsy center in Massachusetts moved to Florida and prefers continuity of care provided through the Level 4 center. To ensure care is covered, in addition to using vacation time to see

providers, the patient must keep coverage in both states.

- In Colorado, there is no other pediatric epilepsy center in a 5-state region. Better coordination of care across states would enable children who don’t have specialized epilepsy care options instate to access appropriate care in a neighboring

state.

One proactive model has worked well to reduce challenges of Medicaid care across state lines:

- In the Cincinnati area, a large Level 4 epilepsy specialty center is championing partnerships with regional medical centers that are not Level 4 epilepsy centers. These partnerships enable better regional coordination of care and patient access to

appropriate levels of care through better utilization of telehealth, technology, and provider communication. AES recommends that CMS encourage similar models and reduce barriers to facilitate such efforts to provide needed out-of-state care for

pediatric epilepsy patients and their families.

II. Optimal Use of Telehealth and Technology

AES encourages development of telehealth, mobile, and other technology solutions to enable improved communication among Medicaid providers, centers, and patients. Telehealth technology has the potential to facilitate access to care, promote optimal quality

of care, reduce costs, and reduce burden for patients and providers. In particular, better availability of e-medical records and communication flexibility across state lines would greatly facilitate portability of care. A number of the questions on

which CMS seeks guidance in this RFI could be addressed with existing telehealth solutions. By reducing barriers to telehealth use, CMS would see reduced Medicaid costs while improving patient access to quality care.

Examples of telehealth use that is working well include:

- The Veterans Administration (VA) health system’s progressive use of telehealth technology, electronic health records and patient portals, and mobile and communications technology overcomes geographic barriers to care and facilitates care across

state boundaries. An AES member physician at a VA system in Wisconsin explains how the VA system provides care across state boundaries: “Routinely we use video telehealth to local [Community Based Outpatient Clinics] to care for Veterans

with epilepsy in Illinois and Michigan. We also have the ability to do telehealth with Veterans at their homes using either VA-supplied hardware or the Veterans' own devices. This modality allows us to expand our coverage to more neighboring states

and to care for Veterans who regularly travel across North America. Furthermore, within the VA system we are able to use telehealth approaches to provide technologies such as responsive neurostimulation and home seizure monitoring to states and

locations which otherwise would preclude these more advanced tools due to lack of local expertise.”

- Colorado now uses telehealth to cover large geographic areas within the state. Given the geographic proximity to other states without convenient access to epilepsy specialty care, there is great potential for benefits to patients and families –

as well as to CMS – from harmonization of Medicaid enrollment requirements, provider licensure and privileging requirements and processes, and telehealth regulations across state lines. Greater harmonization would reduce patient/family and

provider burden and result in better access to efficient and cost-effective out-of-state care for children enrolled in Medicaid.

- In Washington State, Seattle Children’s Telehealth Program is providing care for out-of-state pediatric patients as far away as Montana, Idaho, Alaska, and Wyoming. In the first 9 months of that program’s pilot, care teams saw 119 patients

in 295 video visits and saved families 48,465 miles of driving to Seattle. See: https://www.seattlechildrens.org/informationtechnology/articles/telehealth/

- The Michigan Pediatric Epilepsy Telemedicine Program is a state roadmap for implementation of telemedicine in delivery of pediatric epilepsy services to underserved populations in rural Michigan. This exemplary model outlines practical steps, needs,

and challenges that can inform Medicaid coordination of out-of-state care and related potential telemedicine benefits. See:

https://www.astho.org/MCH/Case-Studies-and-Resources/Michigan-Telemedicine-Prgm/

III. Particular Attention to Effective Care Components Unique to Children with Epilepsy

AES highlights the need to ensure that critical components to effective care for patients with epilepsy are included in coordination of care across state lines. Epilepsy treatment is complex and typically involves an interprofessional team of care providers.

Particularly important out-of-state coordination of care considerations for children with epilepsy and their families includes:

- Timely access to critical epilepsy medications is sometimes challenging for Medicaid patients who are geographically mobile or those whose residence, pharmacy, and care providers may not be in the same state. Barriers to effective

prescribing and prescription filling across state lines should be minimized.

- Interprofessional teams of care providers are involved in the complex care of children with epilepsy.

Teams may include, for example, physicians (epileptologists, neurologists, pediatric surgeons, psychiatrists, primary care

providers), pharmacists, advanced practice providers, social workers, psychologists, dietitians, and preauthorization personnel). Effective care facilitates support services from an interprofessional team and minimizes barriers to care, even when

health care providers are in different states and/or at different centers.

- Mental/behavioral health services are an often underappreciated but critical component of epilepsy care that reduce comorbidities and should be fully supported. Out-of-state care coordination should not present an added barrier to

accessing this care, especially for those Medicaid patients and families whose geographic locations or local availability of services are especially challenging.

- Transition of care from pediatric to adult services is a challenging transition for patients and families, even under the best circumstances. Advance planning and careful coordination of care among patients and families and their

pediatric and adult epilepsy care providers are critical. Barriers and delays with less-than-optimal coordination of Medicaid care across states during age and/or geographic transitions put patients at risk and increase ultimate overall costs

of care.

Two globally important reports underscore the complex medical needs of patients with epilepsy, the importance of multidisciplinary care, and the need for improvements in delivery and coordination of care – all themes that AES highlights through

the recommendations and examples in these comments:

An example of a significant common lapse in coordination of care across state lines that presents a barrier to continuity of medication access for patients with epilepsy:

- Care providers report that 90-day lags to fill prescriptions are not uncommon for patients with epilepsy who reside in a different state than providers. Delays in access to medications place patients at risk, may greatly increase overall costs of

care, and are particularly unacceptable for newly diagnosed patients with epilepsy, for patients relocating to another state, and for pediatric patients with epilepsy who are in transition to adult care.

IV. Adequate Reimbursement to Providers to Support Cost-Effective, High Quality Care

AES urges CMS to support the complex care for epilepsy patients at coverage levels that meet cost of care, rather than current coverage at approximately 60% of actual costs. Current scenarios mean that higher volume equates to higher revenue losses for

providers. Providers should not need to take a loss to care for Medicaid patients. A consequence of inadequate reimbursement is that too many practices restrict the number of available Medicaid patient slots, effectively limiting patient access to

care and driving higher overall costs secondary to gaps in needed care.

The following data and examples illustrate the negative patient access consequences of inadequate reimbursement.

Kaiser Family Foundation Data on Medicaid-to-Medicare Fee Index, 2016, state by state:

- For all services, the US ratio is 0.72, and state ratios may be as low as 0.38

- For primary care services, the US ratio is 0.66, and state ratios range may be as low as 0.33

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid-to-Medicare Fee Index, Timeframe: 2016. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-to-medicare-feeindex/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

Examples of barriers to adequate provider reimbursements reported by epilepsy care providers:

- In Colorado, an adult epilepsy center and pediatric epilepsy treatment program at a large academic center reports that the already-significant challenges of transitioning patients with epilepsy from pediatric to adult care are exacerbated by

inadequate Medicaid reimbursements. The adult care center limits numbers of Medicaid patients accepted for care, and the result is patient wait times of up to 6-12 months for access to specialized epilepsy care teams. To ensure essential care

needs are met, centers resort to keeping Medicaid patients in pediatric care while awaiting access to adult care or rely on primary care providers, even though primary care providers do not have the specialized expertise and multidisciplinary

care teams needed for optimal care of patients with epilepsy whose care needs are complex.

- An epilepsy specialty care provider in a large urban area in Texas reports a scenario where pediatric Medicaid epilepsy patients are referred to a Level 4 specialized epilepsy care center but are effectively unable to access that care due to the center’s

limits on Medicaid patient numbers. Consequently patients are forced to seek alternate care at a county hospital with less expertise in complex epilepsy care needs.

Published studies highlight additional barriers to specialty pediatric care access for patients with epilepsy who have public insurance:

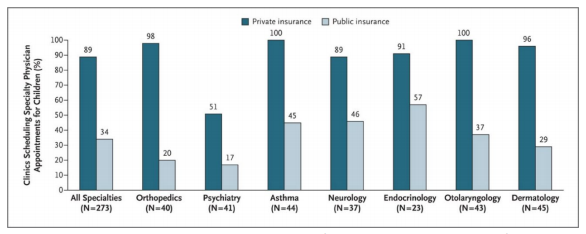

- In a “secret shopper” style study, calls were made to clinics accepting both public (MedicaidCHIP) and private insurance to request appointments for pediatric patients with conditions across seven specialty areas. Overall across specialties,

66% of public insurance patients were denied an appointment versus only 11% of private insurance patients. Average wait times were 22 days longer for children enrolled in public insurance programs versus private insurance. For pediatric patients

reporting new onset afebrile seizures who sought neurology specialty care, the results were only slightly better: 54% of those with public insurance were denied an appointment versus 11% of those with private insurance. Wait times averaged 15

days longer for patients with public insurance versus private. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Clinics Scheduling Specialty Care Appointments for Children, According to Type of Insurance.

Source: Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Auditing access to specialty care for children with public insurance. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jun 16;364(24):2324-33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1013285. PMID: 21675891.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1013285

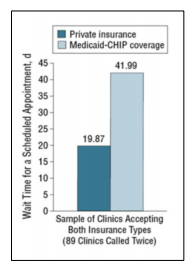

- In a study with a similar design, on average, at academic clinics, Medicaid-CHIP patients would wait over twice as long for an appointment than private insurance patients. Of calls requesting appointments, 57% resulted in discriminatory denials of

appointments to Medicaid-CHIP patients, although discriminatory denial rates were lower at clinics affiliated with academic medical centers. See Figure 2

| Figure 2. Wait Time for a Scheduled Appointment (days)

Source: Bisgaier J, Polsky D, Rhodes KV. Academic medical centers and equity in specialty care access for children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012 Apr;166(4):304-10.

doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1158. Epub 2011 Dec 5. PMID:22147760.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/11484 |

- In a study of barriers to genetic testing for pediatric Medicaid patients with epilepsy, clinicians identified coverage, costs, and health center and payer concerns among the reasons for difficulty in obtaining genetic testing for patients with Medicaid

versus commercial insurance.

Source: Kutscher EJ, Joshi SM, Patel AD, Hafeez B, Grinspan ZM. Barriers to Genetic Testing for Pediatric Medicaid Beneficiaries With Epilepsy. Pediatr Neurol. 2017 Aug;73:28-35. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.04.014. Epub 2017 Apr 20. PMID: 28583702.

https://www.pedneur.com/article/S0887-8994(16)31047-5/abstract

V. Harmonization of Provider, Facility, and Medicaid Qualification Processes Across States

To reduce barriers to out-of-state care and to enable a more seamless experience for patients and families, AES encourages CMS to harmonize regulations across states. This includes coordination of rules and processes around provider qualifications and

privileging; Medicaid insurance plan provisions and enrollment; medication prescribing and prescription filling; telehealth use and reimbursement; and state licensure, privileging, and malpractice insurance.

Currently what is considered a Medicaid “qualified facility” varies across state lines and is confusing for providers and patients alike. The process for Medicaid enrollment is time-consuming, taking as long as 90 days (when patients with

epilepsy need medications much sooner), and is burdensome for providers and practices. Providers report that the need to obtain a license in another state just to enable participation in that state’s Medicaid program, when the provider will

never practice medicine in that state, is a deterrent. Consequently, large centers often do not support the process for all providers, thus reducing numbers of available providers and limiting patient access to Medicaid care.

Streamlining provider and center qualification processes among states is ultimately more cost effective than the current status. Facilitating access to high-quality care for children with complex medical conditions such as epilepsy averts potentially

much greater burden when needed care is less than optimal or unavailable.

Examples of barriers that could be eased or eliminated by harmonization efforts include:

- A Colorado academic medical center that serves patients in five states and must maintain multiple licensures for the various epilepsy care team providers in different states cites the following barriers:

- State-to-state licensure and documentation requirements vary widely, further increasing cost and time burden to centers and providers.

- Some states take longer than others to process licensure applications, and waiting for hospital licensure and/or hospital or prescribing privileges in a different state often presents a barrier to timely care and compromises optimal care for

patients with complex conditions such as epilepsy.

- Montana scrutinizes licensure applications from graduates of non-US medical schools more closely than Colorado, so licensure is often delayed.

- State Licensure – Varying state licensure regulations and poor coordination among states on licensure make it difficult and expensive for Level 4 epilepsy centers and their providers to obtain and maintain licensure across multiple states.

- Malpractice & State Licensure – Non-aligned intersections between malpractice coverage and varying state licensure provisions also make care across state lines difficult for epilepsy care providers and centers.

- As noted previously, disparities among states regarding types of care that may or may not be provided via telemedicine is a current barrier that relates in part to state licensing and privileging disparities. Harmonization among states would enable

greater telemedicine use where appropriate which could in turn enable cost-effective access to specialized epilepsy care providers for children and families using Medicaid services.

Summary

Pediatric patients with epilepsy represent an important segment of the population with complex medical needs addressed by this CMS RFI. The recommendations and examples AES highlights in these comments are key opportunities for CMS to facilitate high-quality

care for this patient population – care that bridges current gaps, reduces comorbidities, decreases patient and family burden, and encourages good coordination of care – while realizing more cost-effective care with net benefits to CMS.

American Epilepsy Society appreciates the opportunity to provide comments and remains available to answer questions, provide additional information, offer clinical or scientific expertise, or otherwise serve as a resource to CMS.